The legend of Dubuque’s Tom Kelly and the gold he is said to have buried on the bluff that bears his name has piqued the imaginations of treasure hunters for decades. As with most legends, there is often a grain of truth in what is said. What do we know to be true about Tom Kelly and what truths back up the legend of his gold?

The Dubuque Daily Herald carried an account of Tom Kelly’s life on May 16, 1867, the day after his death. The paper’s lengthy account of Tom’s “Eccentricities and History” and “Incidents of His Life” offers a peek into Tom’s life and death.

Tom Kelly was born in King’s Co., Ireland, in June 1808, son of Tom Kelly. He had five brothers and a sister. In 1826, Tom emigrated to Canada and in 1827, moved to Oswego, NY, where he labored on the Oswego Canal. In about 1829, Tom and some of his countrymen traveled down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to New Orleans in an effort to earn enough money to go back to Canada. Traveling back up the Ohio without his friends, Tom was robbed of $210 in gold and was forced to return to New Orleans.

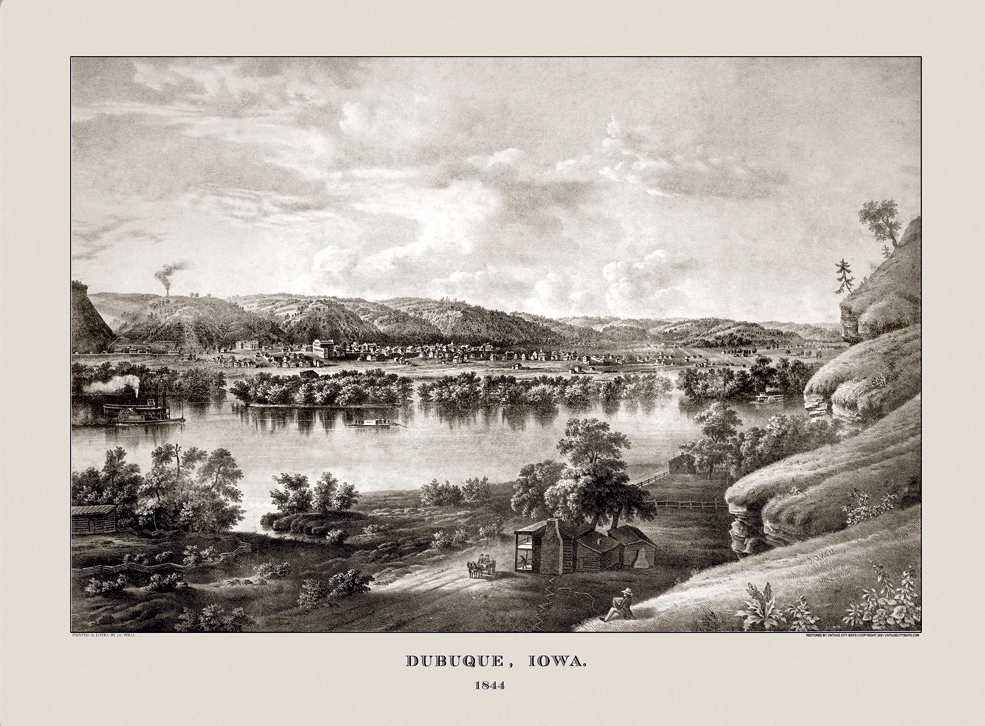

In the spring of 1830, Tom made his way up the Mississippi River to St. Louis and on to the new lead mining region of Galena, IL, where he successfully mined lead, living in a cabin near Sinsinawa Mound. In 1832, he crossed the river into the Dubuque area, which was illegal as the land belonged to the Indians and was off limits before the Blackhawk War. Tom built a cabin near Hill and 5th Streets and began exploring abandoned lead mines, but soldiers forced him to retreat to Illinois until the land was officially opened to settlers and miners.

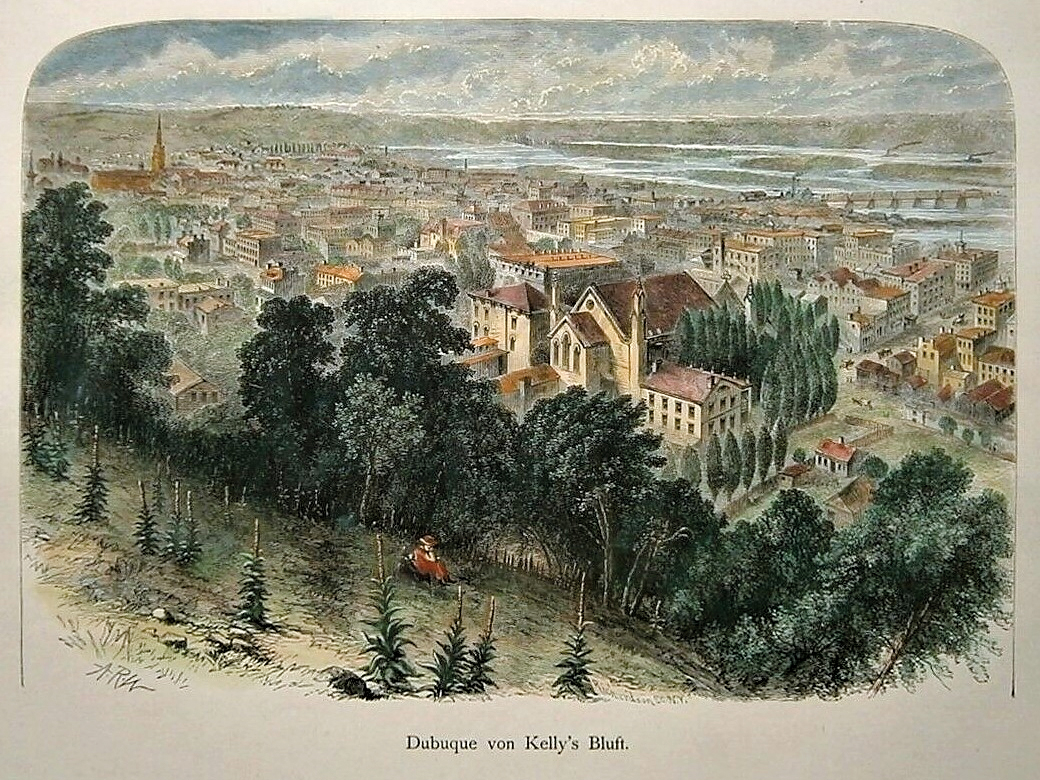

In the spring of 1833, Tom resumed working his Dubuque claims south of the ravine now known as Dodge St. or Highway 20. Discouraged, he moved on to what has come to be known as “Kelly’s Bluff.” The new land, the site of an old Indian encampment, was covered with a heavy oak forest, blue grass, and white clover. Tom soon discovered traces of old mining efforts on the southern slope of the hill.

On his second day of mining he “raised 400 pounds of ore.” The next day he took out 1,000 pounds and then staked off the hill as his claim. Later, he reached the main lode and soon bought adjoining claims until his tract measured more than 30 acres. Tom became a very rich man.

In 1836, Tom travelled to Canada and returned to Dubuque with relatives who had followed him from Ireland. In 1837, he built a smelting furnace on his Dubuque property. Each lead pig produced in the smelter was stamped with his name. Tom eventually discovered another large lode half way up the Third St. Bluff.

Tom floated his ore down the Mississippi on a barge to sell in St. Louis. In 1847, one of his barges sank carrying $15,000 in lead, forcing Tom to travel to New York in 1850 to collect an insurance payout of $10,000. While in New York, Tom shot and killed a man he suspected was following him, and he was sent to the state insane asylum in Utica. In 1854, Tom escaped from the asylum and returned to Dubuque.

In about 1862, Tom dug another shaft on a piece of his land at the top of the hill north of Fifth St. While working the mine, he lived nearby in a cave dug into a bank of clay. According to the paper, his household consisted of “an old stove and a pile of straw with a blanket.”

Tom’s final home was built of stone and boasted two rooms but still lacked the luxury of a window or “a bed-stand though he had a good cellar.” The paper reported Tom mined every day and “always cultivated a garden and probably never starved himself as a matter of economy.” He built an eight-foot fence around his garden, his mine shaft, and his little house, with only a dog and cat for companionship.

In 1865, Tom was judged insane and his brother William was named administrator of the estate. Although Tom was a private man, he was not anti-social, and many disagreed with the insanity ruling. The newspaper reported, “Meeting in the shade of his trees, he would sit for an hour with one or half a dozen friends and talk intelligently on any topic of present or past interest. He was peculiarly fond of having children come in the summer time to see his grove.”

At the age of 58, Tom suffered a serious illness – an event announced in the newspaper the day before he died. Many came to visit, offering help, but his relatives Drs. Finley and Sprague and neighbors were already tending to his needs. In spite of all efforts, Tom died at 3:00 in the afternoon on May 15, 1867. A small funeral service was held the following day and Tom was buried in Linwood Cemetery near his brother Francis.

At the time of his death, Tom had accumulated a pile of ore estimated to weigh 100,000 pounds. is property was valued at $50,000-$200,000. Tom died without a will, but some claim he left a note saying if people wanted his gold, they could look for it.

Tom’s heirs searched “vigorously” for his money and found a pot buried in his cabin containing $4,000 in gold. A year later, a boy found a cache of $1,800 in a tea canister near Tom’s workings. Two other caches of gold have been found to date. In 1900, two boys discovered a small iron chest with $10,000 in eagle and double eagle gold coins.

Is there more treasure to be found? Maybe…

To read this and other premium articles in their entirety, pick up the December 2023 issue of Julien’s Journal magazine. Click to subscribe for convenient delivery by mail, or call (563) 557-7571. Single issues are available in print at area newsstands and digitally on JuliensJournal.com.

Comment here