Sunnycrest Manor, the Dubuque County-owned nursing home, officially opened nearly 101 years ago on August 13, 1921 as a tuberculosis sanatorium – a place where patients could safely convalesce without exposing their loved ones to the dreaded disease. Once called the “white plague” or “consumption,” tuberculosis was at one time rampant in Dubuque and across the United States.

Extant records from Dubuque’s City Cemetery from May 1855 to October 1875 tell the story. Consumption, now known as pulmonary tuberculosis, killed more people than any other cause of death during those years. Of 2,679 entries penned in the sextant’s records, 12% of City Cemetery deaths were due to tuberculosis.

Treating those afflicted with tuberculosis was brought to the forefront in 1906 when a meeting was held in Dubuque to look into establishing a tent colony to isolate carriers of the feared disease. By 1911, a nation-wide campaign was launched to educate folks about the dangers of tuberculosis. Dubuque responded with posters on thirty-five billboards that outlined steps for preventing tuberculosis.

The citizens of Dubuque astutely recognized that something better than a tent colony was needed. In 1916, a meeting of local charitable organizations and social clubs resulted in a public vote to approve a $75,000 bond issue along with a two mill levy to cover bond payment and building maintenance. The bond issue passed.

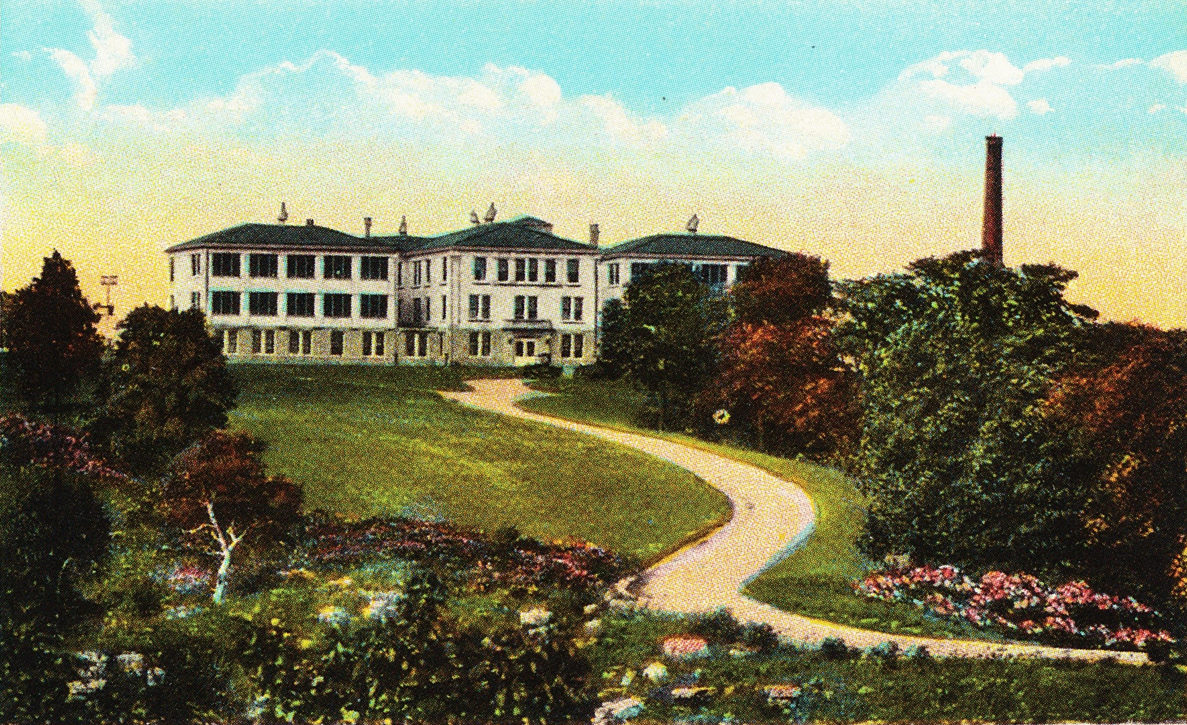

With funding in place, a twenty-six-acre site on a hilltop off Roosevelt St. in Dubuque’s north end was purchased from D.A. Gehrig of Dyersville at a cost of $100 per acre. Before construction got underway, officials thoroughly investigated the layout of tuberculosis facilities in Davenport and Iowa City – along with treatment hospitals in Illinois and Wisconsin – to make sure the sanatorium would be properly built. WWI caused plans to be put on hold at the request of the government, but following the end of hostilities, Dubuque awarded Anton Zwack the $89,000 construction contract.

In May 1919, work got underway on the sanatorium. By October 1920, the facility was completed. Total cost of the project came to $150,000.

The new, three-story building was dedicated on August 13, 1921. Built of concrete with an interior of mosaic tiling, each room was open to fresh air and sunshine. In addition to twenty private rooms and four wards, the facility boasted four offices, two dining rooms, a reception area, a recreation room, three kitchens, and four “sun parlors.” At the time, fresh air and sunshine were considered essential in the fight to cure tuberculosis.

A separate building to house nurses was built nearby. Dr. Jesse Carl Painter, a leading national authority on tuberculosis, was hired as the medical director to oversee Sunnycrest Sanatorium, a position he would hold for thirty-six years before he retired.

Soon the new sanatorium was filled to near capacity with sixty-two patients from a wide variety of backgrounds. Early patients included a nurse, a printer, a movie operator, a machinist, a telephone operator, and several social workers. The patients were between the ages of fifteen and forty years old.

In 1923, Sunnycrest Sanatorium patients were charged $3 per day, according to a listing in the National Tuberculosis Association’s Directory of Anatoria, Hospitals, Day Camps, and Preventoria for the Treatment of Tuberculosis in the United States. The information provided in the directory advised prospective patients and their families that they could reach the sanatorium by using the city’s Eagle Point street car.

Treatment options changed drastically under Dr. Painter. Originally, consumption was treated with the “three Rs” (rest, rest, rest). In the early 1940s, surgical resection of the affected “tuberculosis foci” was advocated along with rest. Later treatment revolved around drugs with the discovery of streptomycin in 1944.

In 1947, Sunnycrest underwent an extensive remodel. The large outside porches were converted to rooms, as treatment with exposure to fresh air and sunshine air was considered antiquated.

In 1954, Dr. Painter was quoted in the Dubuque Telegraph Herald, “The history of the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis is one of changing emphasis. Each method strong while it lasted but each method destined to be replaced by a new one. The concept that a drug might cure tuberculosis was revolutionary in the extreme. Like all new and untried drugs, much study and experimental usage was necessary for some time before the real benefits were finally understood and utilized.”

Between 1930 and 1950, the national death rate from tuberculosis plummeted from thirty to just eight per 100,000 persons. Unfortunately, most patients weren’t admitted to Dubuque’s sanatorium until they were in the advanced stages of the disease. Of thirty-eight patients admitted in 1953, 71.1% were already in the advanced stages. But there was some good news: forty-three patients were discharged in 1953 after an average stay of 332 days.

With new treatments available to effectively cure the disease, the Sunnycrest patient population continued to drop; eventually, the facility stood nearly empty. Just prior to his retirement in 1957, Dr. Painter announced the closing of Sunnycrest as a tuberculosis sanatorium. The few remaining patients still housed in Dubuque’s sanatorium were transferred to the Oakdale Sanatorium in Iowa City.

In 1959, just two years after closing, the former tuberculosis sanatorium reopened as the Dubuque County Nursing Home for the care of indigents. In 1968, an addition to the facility was built, and the name was changed to Sunnycrest Manor in 1976.

In 1980, the Sunrise Intermediate Care Facilities and Intellectual Disabilities Unit was opened at Sunnycrest, earning the facility the distinction of becoming one of the first “community-based intermediate care facilities for persons with intellectual disabilities.” In 2001, Sunnycrest Manor implemented the “Home and Heart” program, a “model example of nursing home culture change which recognizes individuality and honors resident choices,” continuing the long tradition of offering care to those who need it most.

This article is part of the Shades of Dubuque series, sponsored by Trappist Caskets, hand-made and blessed by the monks at New Melleray Abbey. More at trappistcaskets.com.

Comment here