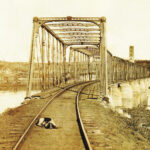

No matter where I begin my stroll along Dubuque’s Mississippi Riverwalk, I always seem to wind up on a bench at the northern end, right next to the old railroad bridge. I peer down the track to the little white bridge tender’s shack and try to imagine what the tender on duty is up to. Bridge tenders work alone, and someone is always on duty. Each shift begins with a hike down a narrow catwalk to the control shack located in the middle of the swing span. The tender walks past original, historic pieces of the bridge as well as new steel that was part of bridge owner Canadian National Railroad’s multi-million dollar upgrade.

The bridge has a long, fascinating history. Most historians point to Dubuque attorney Platt Smith’s buggy accident way back in 1867 on a frigid winter night as the reason the bridge was built the way it was, as well as the reason the bridge is still standing today.

When Smith’s buggy wheel hit a cast-iron lamp post, the light fixture shattered. Budding industrialist Andrew Carnegie used Smith’s accident to convince Dunleith and Dubuque Bridge Company officials to hire his Keystone Bridge Company to build the long-awaited railroad bridge across the Mississippi River, connecting Dubuque, IA, with Dunleith, now East Dubuque, IL.

Carnegie asked the board to compare a steamboat colliding with a bridge made entirely of cast-iron to a collision with a bridge built with a wrought-iron upper chord. He claimed, “In the case of the wrought-iron chord, the bridge would probably only bend; in the case of the cast-iron, it would certainly break and down would come the bridge.”

Convinced, the directors signed a contract with Carnegie on January 14, 1868. That same day, they also hired bridge masonry specialists Reynolds, Saulpaugh, and Company of Rock Island, IL, to build the bridge substructure and to blast a railroad tunnel through the bluff on the Illinois side of the river.

Two weeks later, civil engineers pounded a row of stakes into the thick river ice to mark the location of the bridge. By the end of February 1868, explosions from the tunnel blasting in Illinois and the thud of two, steam-powered engines driving piles through the ice into bedrock echoed across the Mississippi River valley.

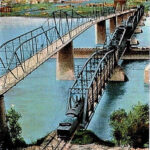

Work on the 1760-foot main bridge, the 360-foot swing span, and the 844-foot tunnel continued throughout the spring, summer, and fall of 1868. The project was completed in December, a month ahead of schedule, at a total cost of $800,000.

During a test run on December 22, the bridge passed with flying colors and “scarcely a tremor was felt.” On New Year’s Day, 1869, hundreds turned out for the official opening of the third “all metal truss” railroad bridge to cross the Mississippi.

In January 1872, after Dubuque’s sloughs were drained, Carnegie’s bridge company built seven identical cast and wrought iron spans to replace the 2400-foot wooden approach trestle that had crossed the wetlands. Those spans were later eliminated. Two of those spans have found new homes in Dubuque County recreational areas. One crosses the pond at John G. Bergfeld Recreation Area in Dubuque Industrial Center West. Another serves as a rest stop alongside Heritage Trail, a popular hiking/biking trail just north of Dubuque. A third span can be found near Fairgrounds St. in Vicksburg, Mississippi.

By 1898, Carnegie’s railroad bridge was in need of repair, and a $200,000 renovation began. The swing span was rebuilt, the approaches were reconstructed, new track was put down, and the superstructure received a major overhaul.

Originally, it took six men pushing a huge turnbuckle to move the 600-ton swing span. Records show that in1878, 3139 steamboats and 884 barges passed through the bridge. In 1892, the swing span was electrified – then only three men were needed to run the bridge. Now, a single bridge tender remotely opens and closes the swing span.

Federal law gives river traffic priority over the railroad. Modern safeguards have been put in place to prevent accidents, but that wasn’t always the case. In 1886, the engineer of a west-bound freight train failed to notice the span was open until he reached the final approach. He whistled for an emergency stop and threw the engine into reverse. When the engine was a mere 20 feet from the end of the track, the brakeman and fireman jumped while the engineer frantically tried to stop the train. The cowcatcher and front wheels dropped into the void, dragging the engine and two cars into the Mississippi. The engineer survived with cuts and bruises.

Until 2002, tenders had to leave the safety of the bridge shack to pull big connecting pins on each end of the swing span and then raise four supporting legs, two on each end of the span. An electric motor turned gears to swing the span 90 degrees onto a permanent structure located parallel to the riverbank. Now, the tender uses remote controls to open and close the bridge by powering a complex set of gears. The final gear that moves the span is more than 240 feet around.

Bridge tenders have come and gone since Dubuque’s railroad bridge opened more than a century and a half ago, but the bridge retains much of the original 1868 structure and looks nearly the same as it did following the 1900 renovation. Andrew Carnegie would be pleased to know that his 152-year-old railroad bridge is still in use, serving as a vital link across the Mississippi River.

This article is part of the Shades of Dubuque series, sponsored by Trappist Caskets, hand-made and blessed by the monks at New Melleray Abbey.

Comment here