The small group of young people from Lenox College in Hopkinton, Iowa, was exhausted. On this cold but sunny February day in 1911, they had a fine bobsledding party, sledding down some of the hills near their campus in this small Delaware County town. Now the sun was setting, and it was time to return to their college rooms and prepare for the next day’s classes. But there was a problem, one of these boys, who was also doing some janitorial work for the school, could not find his key ring which had keys to several major buildings on the college campus. The students joined in the search, but the key ring could not be found. Discouraged, all but two of the young people left. These two remaining students, both freshmen boys, continued to look and eventually found the missing keys.

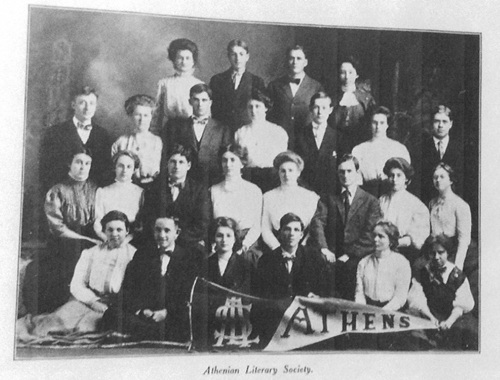

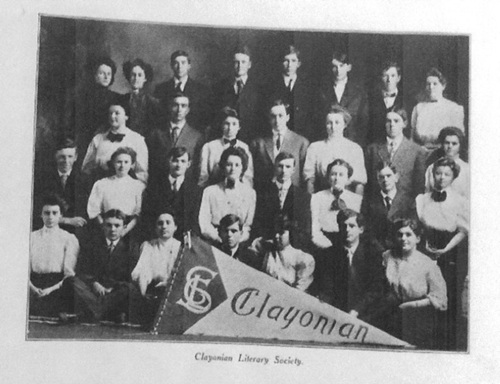

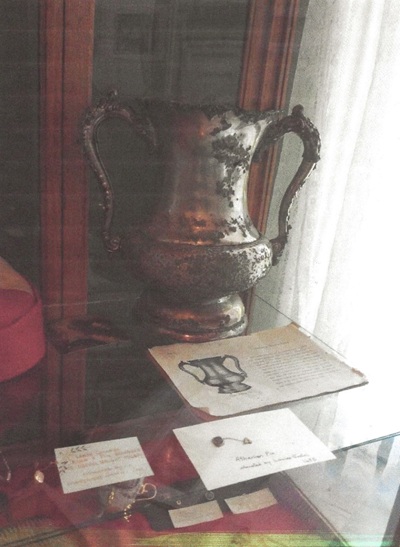

Some weeks before, the annual debating contest on the campus took place. It was a rivalry which pitted the Athenian Literary Society (Est. 1862) against the Clayonian Literary Society (Est.1877). These two literary, parliamentary and social organizations were among the oldest such chartered groups of their kind in Iowa and had been on the campus of Lenox College for decades. One of many purposes of the groups were to “learn the lessons of poise and leadership.” Members of both Lenox College groups tried to excel over the other in all kinds of contests but the most important was the annual debate contest. Tensions were always high as this contest drew closer. Debate questions might be something like, “Resolved that the average young man today (1911) has not as great opportunities to make life a success financially as his forefathers.” The contest was so important that a silver-plated travelling trophy called the Faculty Debating Cup, had been created in 1908. Although it was a travelling trophy, it also had the stipulation that, should one of the two groups win for three consecutive years, it would remain in their trophy case forever with the names of the participants engraved upon it.

Both the Athenians and the Clayonians had their own campus halls “which are tastily decorated and nicely furnished, including pianos” on the third floor of the newly built Doolittle Hall (1901.) The debate competition was intense, and it was thought the trophy might go back and forth between the two for many years, but it didn’t happen that way. The Clayonians won it the first three years of the competition and according to the rules, it became theirs and they joyfully took it to their Society room. The Clayoninans were proud of this accomplishment and certainly made the Athenians, along with the rest of the campus, aware of this victory. They had their names engraved on the trophy. The sting of jealousy was prevalent amongst the defeated Athenians.

In the fall of 1970, an old man, now in his early eighties, returned to the old Lenox Campus. The college had been closed since 1946 due to financial problems and a lack of students. The buildings, however, had been maintained over the years. Some had been used by the local public school for a period shortly after the college closed. When they were no longer needed by the school district, the Delaware County Historical Society acquired them. When the old man returned, the campus was now quiet but did remain as a place of remembrance.

The man, Herbert R. Bush, now of Minneapolis but originally from Olin, Iowa, had been an eighteen-year-old student at Lenox College in 1911 and wanted to see the campus and town one more time before his life ended. But he also had a story that hadn’t been told before, a secret he had kept for sixty years. He spent time in Old Main, Doolittle Hall and Clarke Hall and walked around the campus. Bush was then given a tour of the town by the Delaware County Historical Society Director, Laura Morgan. He couldn’t keep the secret any longer and confided that it was he and another student, Dean Morgan, both Athenians, who had found the missing key ring in the snow so many years before. They had then gone to Doolittle Hall, used the key to open the buildings and the Clayonian Society room and had stolen the coveted debate trophy. They buried it, perhaps intending to dig it us at some point, but the uproar on the campus made them fearful that they might be dismissed from the college or worse. They never told anyone, eventually leaving the college and Hopkinton to continue their lives. Perhaps not even Park Orcutt Bush, his wife, and a teacher in Hopkinton when they married in 1913, had been told.

It was raining on the day of the tour and so Mr. Bush didn’t leave the car but, as they drove by, did point his finger in the direction of St. John’s Lutheran Church, not far from the Lenox campus at the corner of 2nd Street SW and Carter Street SW. The church building which had been there in 1911 was still in the same location where it had stood since it was built in 1860. Bush said they had buried the debate trophy there and, as far as he knew, it was still there unless it had been discovered over the years. He didn’t disclose an exact location and may not have remembered exactly where it was buried.

Some days after Mr. Bush’s revelation, the historical society director shared this intriguing information with some of the Hopkinton residents. Some of them used metal detectors and tried to locate any metal objects under the grounds of the church yard but didn’t have any luck. It was decided that either the old man had the location wrong or was a little confused about some of the facts.

When researchers tried to learn more, they were stymied. The entire incident seemed to have been hushed up by the college shortly after it had occurred. This same debate trophy was pictured in the college catalogues of the three years prior to 1911 but nothing thereafter with no explanation. The loss was probably embarrassing to the Presbyterian affiliated college, and the president and board did not want people to think of their college as being one linked with thievery. It was said that even the school newspaper, The Nut Shell, never mentioned the incident.

Lenox College was certainly a proud institution. One of their former students, Thomas H. Macbride would later become the president of the University of Iowa in 1914. Samuel Calvin was a Lenox instructor during its early years. He later became the state geologist and was honored by having a building on the University of Iowa campus named after him. The school was also attended by the father of the famous Iowa painter, Grant Wood, among many others who attained some semblance of fortune or fame following their attendance at Lenox.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that a man named Sam Carter, descendant of Henry Carter, a man who had laid out the town of Hopkinton and helped start Lenox College in 1859, brought a powerful metal detector from Dubuque to the Lutheran Church site. The old church structure had been demolished in 1973 and replaced with a new church. Carter, and others, remembered the month (February) the supposed theft had taken place thought just where would the two young men bury a sizable trophy in the dead of winter? One in the group remembered that old-timers had spoken of a lean-to that had been used for the horses that brought people to church which had been in the back of the church lot. There the soil might have been warmed by the horses and could be more easily dug into during that cold day in 1911. And sure enough, the detector signaled that it had found something and there, under about 30 inches of soil, was the debate trophy. The mystery had been solved. The once prized trophy, tarnished and a little worse for wear, could return, once again, to one of the rooms in the college campus buildings.

But there is an additional mystery. Personnel at the history center tell of another missing relic from the same time. This one, a bust of President Lincoln that was also given for oratory, was stolen, not once, but twice. The first time it was found under a porch at Clarke Hall, the women’s dormitory, with Lincoln’s famous sizable nose broken off (which was promptly mended) but then once again it went missing. Could it, too, also be hidden under the soils of the campus or town?

This story was submitted by Julien’s Journal reader Paul C. Juhl.

Some information courtesy of Cedar Rapids Gazette, July 19, 1981

Comment here