The Mathias Ham House on the corner of Lincoln Avenue and Shiras Boulevard ranks as one of Dubuque’s historic treasures – right up there with the Shot Tower, 4th St. Elevator, and Eagle Point Park.

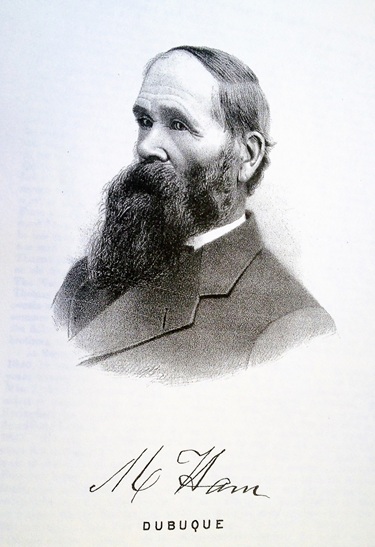

Mathias Ham, one of Dubuque’s earliest pioneers, already had several careers under his belt by 1833 when he settled in what would become Iowa Territory.

In 1822 at the age of 17, he left his Missouri home to work on the Mississippi River, boasting to his mother that he wouldn’t return until he had accumulated $20,000.

Ham worked his way upriver to Galena, Illinois, and started amassing his fortune. After soldiering in the 1832 Black Hawk War, he became a riverboat captain and was the first to deliver a boat load of dressed pork from Galena to New Orleans.

Ham then turned to lead mining and smelting. By 1836, he owned part interest in a Snake Diggings, Wisconsin smelter and operated a Mississippi River ferry between the smelter and his property in the Eagle Point district north of Dubuque. Ham soon branched out into lime kilns, brickyards, and construction – up and coming industries in the booming city of Dubuque.

In 1837, Ham travelled south to Kentucky where he married Zerelda Marklin. Returning to Dubuque, Ham built the city’s first public school with lumber he donated. To support his construction business, Ham cut wood from his acreage along the river, including land now known as Chaplain Schmitt Memorial Island. Some historians claim that as Ham cleared wood from his riverfront land, he planted cabbage to sell to Dubuque’s sauerkraut-loving German population, earning him the nickname “Sauerkraut King.”

Ham built a two-story, Nauvoo limestone home on a knoll overlooking the river in 1839 and began to raise a family in the six-room structure. In 1855, Zerelda died, leaving Ham with five children. The following year, Ham won the subcontract to supply limestone for the construction of the Dubuque Federal Customs House, a facility made necessary by increased steamboat traffic. The government contract allowed Ham to decide which stones were suitable for the project and let him keep those that weren’t.

Ham hired architect John F. Rague to design his house and used the rejected limestone to build a 23-room, three-story mansion adjoining his original farmhouse. Unfortunately, a disgruntled worker burned the interior of the finished home in 1856. After rebuilding in 1857, Ham hosted gala parties, but lavish entertainment ended when he lost his fortune in the financial crash later that year. Ham never regained his wealth, but he remarried in 1860 and fathered two more children. He died at home in 1889 at the age of 84.

Ham’s mansion changed hands many times in the years following his death, but a family member always remained in residence. In 1905, two Chicago doctors rented part of the mansion for their Kegler Cancer Cure Sanitarium. After two years, the venture failed, and the hospital closed.

In 1912, the City of Dubuque bought the Ham mansion for $9,500 from Ham’s daughter Sarah. The Dubuque Park Board used the house for offices and as the park superintendent’s residence. Park Superintendent Richard Kramer and his family lived in the Ham mansion from 1959 to 1963.

Mary Jo Kramer Vogt was five years old in 1959 when her family moved into the Ham House where her father had his office. The Kramers used the porch entrance to access the laundry room, kitchen, living room, and two bedrooms on the first floor. “We used the servants’ stairs to get to the second-floor bathroom that had a bathtub,” Mary Jo recalled. “We didn’t go into the foyer, and we didn’t use the main steps. Dad had a train set on the third floor. The rest of the house was decrepit, and we weren’t allowed to use it. The house was full of bats and mice. Mom finally had enough when she found a dead bat in my baby sister’s crib. We moved out of the Ham House the day President Kennedy was shot in November 1963.”

The Dubuque County Historical Society took over operation of the Ham House in 1964 and in 1976, Ham’s mansion was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Today, the Historical Society offers summer tours of the Ham House, offering visitors a peak at what passed for luxury in the 19th century.

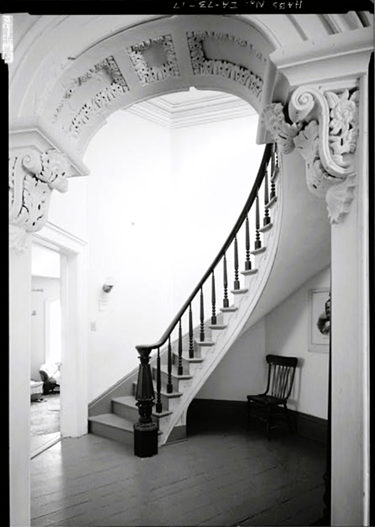

The rooms boast high, 14-foot ceilings ornamented with plaster rosettes and moldings. Six-inch pine was used for the flooring while the stair rails, newel posts, and spindles were built of black walnut. During the 1930s, WPA workers installed maple flooring on the first floor and closed some fireplaces. Most of the rest of the home is original. The Ham family took their furnishings with them when they moved. Now the rooms are filled with fine furniture and artifacts donated by some of Dubuque earliest and wealthiest families.

Some claim the house is haunted. Over the years, Historical Society employees have reported icy winds on the third floor, odd noises, unexplained lights, and even strains of music emanating from a non-functioning pump organ.

Speculation about a Ham House ghost points to a chilling story involving a pirate captain. The story says Ham liked to watch activity on the Mississippi from the cupola high on top of his mansion. One day Ham spotted pirates harassing boats and alerted authorities who captured the pirates. The pirates figured Ham was responsible for their capture and vowed revenge.

One night in the 1890s, Ham’s daughter Sarah, alone in the mansion, was reading in her third-floor bedroom when she heard a prowler. The footsteps faded, but Sarah was so spooked she arranged to hang a signal lantern in her window to alert neighbors if she needed help.

The prowler showed up again the next night. Sarah called out to the intruder but received no answer. She locked her door, hung the signal lantern in the window, and readied her gun. When the intruder pounded up the stairs, Sarah fired two shots through her bedroom door.

The neighbors saw Sarah’s signal lantern and rushed over. Although they didn’t find the prowler, they spotted a blood trail. Blood spatters led from outside Sarah’s bedroom down to the river where a pirate lay dead.

Does the murdered pirate’s ghost haunt Ham’s mansion today? Maybe – or maybe its Mathias Ham’s ghost keeping an eye on his property. Or maybe it’s just the creaks, groans, and leaky doors and windows that go along with a more than 180-year-old house.

Read Julien’s Journal, CHOICES For Fifty Plus and Tri-State Home TRENDS from the Comfort of Your Home!

Click Here or call 563.557.7571 to subscribe for convenient delivery to your home or business by mail of all three magazines for one low subscription price.

Single issues are available in print at area newsstands or Click Here to read the digital version on JuliensJournal.com.

Comment here