Joseph Bartlett Dorr wasn’t a native Dubuquer, but he is counted among the city’s Civil War heroes. Born in New York on August 5, 1825, Dorr came west with his father and sisters and settled in Jackson County in 1847.

At the age of 23, Dorr became editor and proprietor of the Jackson County Democrat. He continued working in the newspaper business, first in Bellevue and later in Dubuque where he purchased an interest in the Dubuque Herald. He sold his share of the newspaper during the winter of 1860-61, just a few months before the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, marking the beginning of the Civil War.

When President Lincoln called for 75,000 militiamen to put down the “insurrection,” Dorr came forward and helped raise the 12th Iowa Infantry. They mustered in on October 17, 1861, with Dorr as 1st lieutenant and quartermaster. The following month Dorr left his wife, son, and daughter in Dubuque to take up the cause of the Union.

The 12th Iowa moved south from St. Louis to Cairo, IL, to Fort Donelson, TN, where they engaged in a siege that ended with the fort’s capture. Their luck ran out at the bloody Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee, on April 6, 1862, when Dorr and 400 soldiers were captured and imprisoned in a Montgomery, AL cotton shed.

Dorr survived the rancid food, disease, and wrath of brutal guards and escaped during a late May 1862 prisoner exchange. He made his way back to Dubuque where he helped raise the 8th Iowa Cavalry. In the spring 1863, Dorr was promoted to colonel, and in October, he and the 8th Iowa headed south.

Col. Dorr was wounded while tracking down guerillas near Waverly, TN, in March 1864. However, he was still able to participate in the Atlanta campaign.

In May 1864, the Dorrs welcomed their third child, a boy the colonel would never see. The following July, Dorr wrote to his wife with a great sense of foreboding, “Our country must be saved though you and I never meet again and I see our children no more.”

A Confederate minie ball tore into Col. Dorr’s body on July 29, 1864, during a battle near Lovejoy’s Station, GA. Despite his injury, Dorr postponed medical attention and insisted on being tied into his saddle so he could urge his men forward. His men came under deadly fire, and “the head of the column went down like grass before the scythe.” The regiment was forced to withdraw.

The next day, Col. Dorr and his men were captured near Newnan, GA. Although many were sent to the notorious prison camp at Andersonville, Dorr and the other officers were imprisoned in Charleston, SC.

Dorr was exchanged in November 1864, and he rejoined his regiment in Alabama. By April 1865, he was well enough to accompany the 8th Iowa and others on Croxton’s Raid, a trek that covered more than 650 miles, crossed four major rivers, destroyed ironworks, mills, and factories and captured 500 prisoners.

Following Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865, Col. Dorr was sent to Macon, GA to perform duties of “pacification.” His wounds and the hardships he had endured on the raid had ruined his health. Only sleep and morphine relieved his physical torment.

On May 24, he wrote his last letter home, “lying on [his] back and in considerable pain.” He beseeched his wife to “give my love to Father, sisters, and friends. Kiss the children for me.”

Col. Joseph B. Dorr died four days later on May 28, 1865 – he was 39 years old. Dorr’s fellow soldiers accompanied his body to the train station for his return home. Following a funeral service at Dubuque’s Congregational Church, the Masons and the Germania Band accompanied Col. Dorr’s body to his final resting place in Linwood Cemetery.

Col. Dorr’s short life was certainly extraordinary. Entries from the diary he kept while a prisoner in Montgomery, letters he wrote home, and details he penned chronicling the 8th Iowa’s participation in the Civil War have survived and provide details of the last three years of his life.

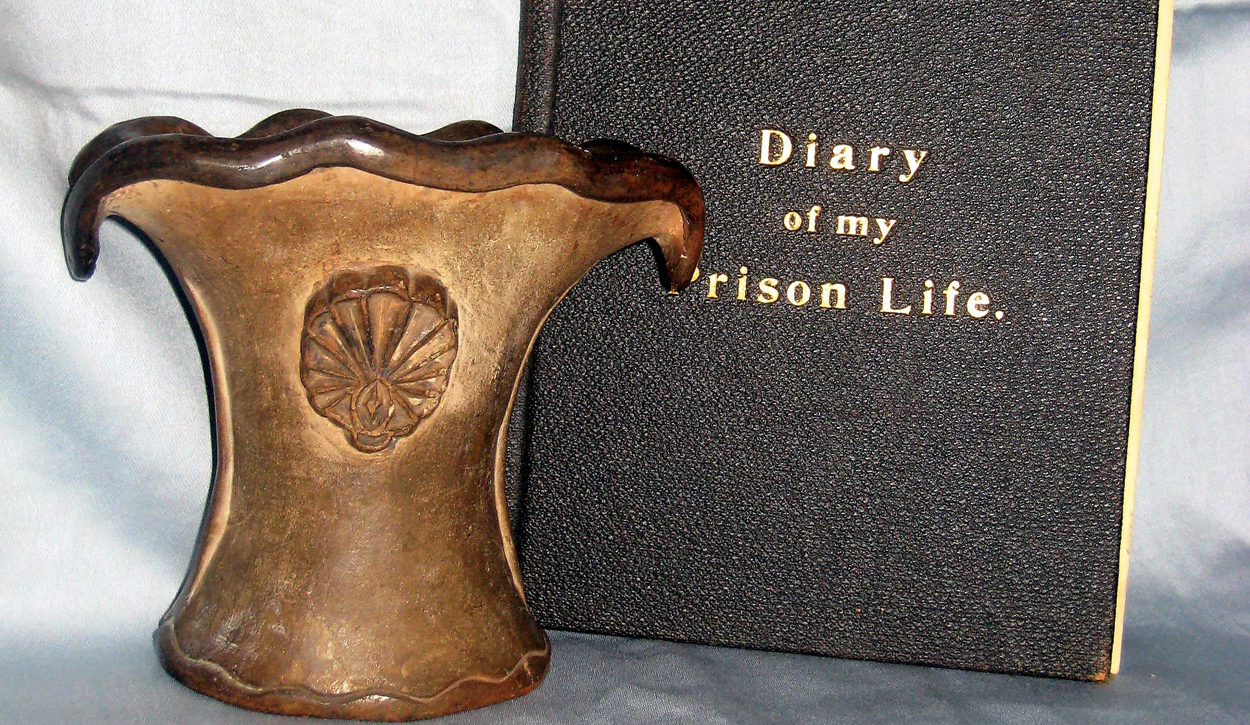

Dorr’s Montgomery prison journal was published in 1877 by his son Charles under the title Diary of My Prison Life. While all the entries are fascinating, I’m especially drawn to the notation Dorr wrote in May 1862:

Wednesday, May 14 – Nothing occurred today. I have varied my amusements for a few days by making a couple of flower vases for little four-year-old Jennie at home. Heaven keep her and my loved ones at our Iowa hearthstone.

In an earlier entry, Dorr wrote that the prisoners “with true Yankee sharpness and industry… found a way to relieve the rebels of their spare change.”

The captives “found a few inches below the surface of our jail yard a tough clay, and of this they are making pipes and selling to poor trash.”

Dorr boasted, “Some creditable work has been done.”

What happened to the clay flower vases Dorr made for his daughter? A little research discovered they were passed down through the generations. One was lost in a fire, but the last remaining vase made its way to Dorr’s great-granddaughter Ethel Dorr Rubino (1927-2017) of Norwalk, Connecticut. I visited with Ethel in 2013, and she allowed me to hold the surviving, age-darkened, clay vase.

The miniature vase was skillfully crafted and engraved “Montgomery 1862” near the base. The heirloom stands just four inches tall – the perfect size for a four-year-old. As I held the tiny vase, I tried to picture the delight little Jennie Dorr must have felt when her father presented her with the pair of vases he had molded while a captive in a southern prison. I imagine little Jennie was just as thrilled with the vases back in 1862 as I was with my success in tracking down the surviving heirloom and holding it in my own hands more than 150 years later.

This article is part of the Shades of Dubuque series, sponsored by Trappist Caskets, hand-made and blessed by the monks at New Melleray Abbey.

My name Benjamin Davis. I have a 8th Iowa Calvary promotion order for Eighth Corporal William J. Rice signed by Col Dorrr.