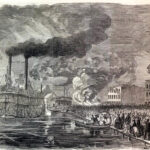

On April 22, 1861, more than 3,000 Dubuque residents gathered at the city’s Jones Street levee on the Mississippi River to see the Jackson Guards and Governor’s Greys off to the Civil War. The crowd cheered as the steamboat Alhambra pulled away from the shore, swung into the current, and headed downriver to Davenport, the headquarters of the Iowa Regiment.

Dubuque’s twenty-four-year-old Alexander Simplot quickly sketched the incredible scene and sent his pencil drawing to Harper’s Weekly, a national illustrated newspaper with a circulation of 115,000. The editors published Simplot’s sketch on May 25, 1861. So impressed with his talent, they hired him as a “special correspondent.” Over the next two years, Simplot would travel along the Mississippi River for Harper’s, sketching battle scenes as quickly as possible to capture the action. Harper’s published 51 of Simplot’s sketches before illness forced him to leave the battlefields and return home to Dubuque.

Simplot was born on January 5, 1837 in a log cabin on Dubuque’s Main Street. “Alex was from a large, wealthy family which originated from France,” wrote Simplot’s grandson John Simplot in 2005. “They were on their way to New Orleans but liked Dubuque so well they decided to stay.” Simplot’s father, a wealthy merchant, eventually became an Aldermen under the city’s first mayor.

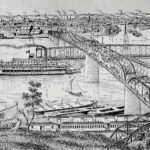

Even as a boy, Simplot showed a talent for drawing. Unfortunately, his playmates made fun of his drawings and his relatives discouraged his efforts. Often, young Simplot turned away from his sketchpad and joined his gang of friends at Dubuque’s busy steamboat landing. “We had no trains to meet or depots to visit and could only judge of the stir in the outer world by the coming of the stage coach and the passing steamers laden with passengers and freight,” Simplot wrote in 1909. “We seldom missed a boat during the early hours of the night. I know of nothing which struck my imagination more vividly than the appearance of one of our large steamers, approaching at night with bows headed directly for you, with its two large open furnaces, one on each side, like huge fiery eyes, and the thick black smoke surging from the chimneys, with the bellowing cough of the escaping steam, aglow at the landing as some base monster out of the darkness.”

Simplot, however, wasn’t allowed to spend all his time at the steamboat landing because his parents valued education and enrolled him in local schools. Later, they sent him to Rock River Seminary at Mount Morris, IL. In 1856, Simplot enrolled in the “Classical Course” at New York’s Union College and received a degree two years later.

In the summer of 1861, Harper’s commissioned Simplot to set up headquarters near Cairo, IL, at the juncture of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. Here, the young artist sketched fortifications, camps, and soldiers, relying on his extensive knowledge of the river and his expertise in drawing steamboats to portray the vessels which would soon serve as troop transports and converted warships.

Initially, Simplot and the other correspondents had little action to report and began calling themselves the “Bohemian Brigade,” which typified their carefree existence before the western campaign intensified. Activity picked up in the winter of 1861-1862 when Simplot covered the army under General Ulysses S. Grant. Simplot was appointed assistant engineer in the War Department and in that position was able to observe and portray many Mississippi River battles.

Simplot’s career as a Civil War illustrator peaked at Memphis, TN, in June 1862 when Union forces assembled a fleet of ironclads that defeated eight Confederate ships. Simplot was the only artist with the northern forces, and his illustrations were the only depictions of this crucial victory.

A few months after Memphis, Simplot developed a chronic case of dysentery and early in 1863, he left the army and returned to Dubuque. Two years later, he sketched one more drawing for Harper’s – Grant’s triumphal return to Galena on August 18, 1865.

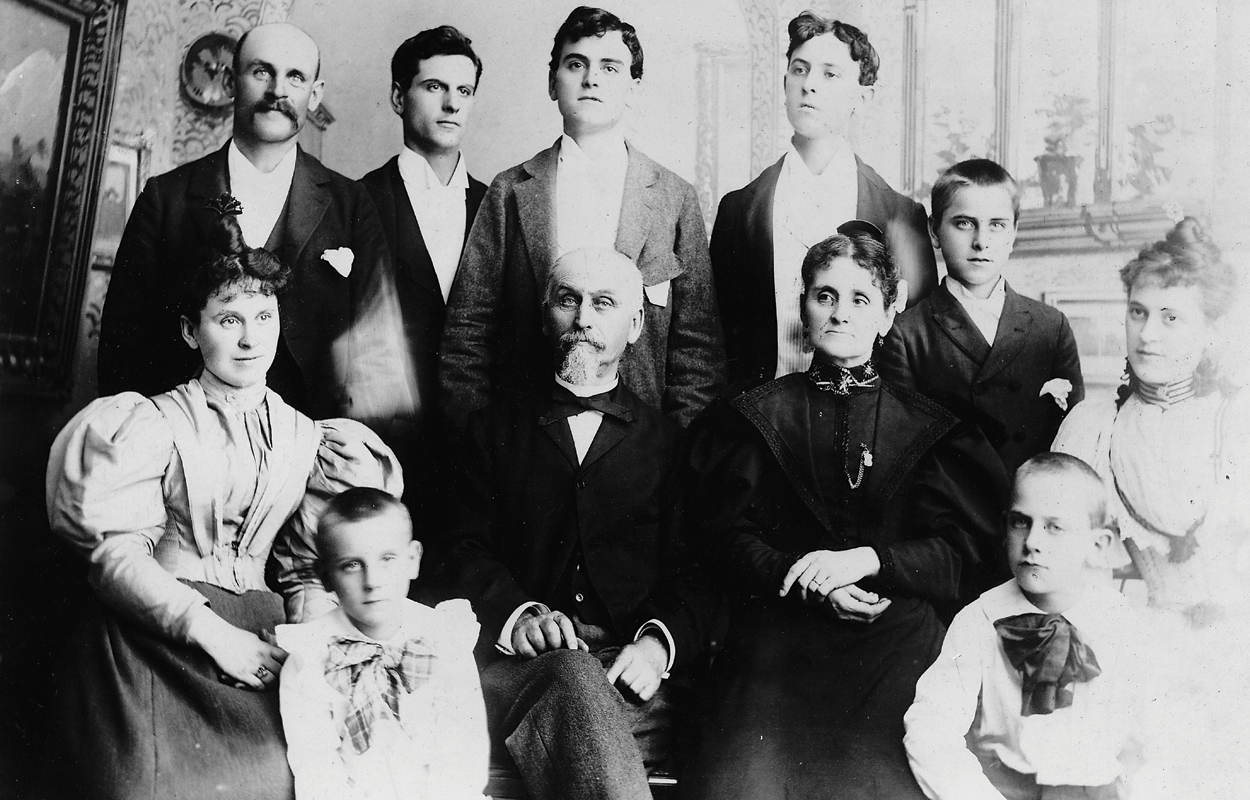

Back in Dubuque, Simplot taught school and in 1866, married Virginia Knapp, one of his students. Together they had nine children. Later, Simplot worked alongside two of his brothers in the dry goods business, but the work didn’t appeal to him. He soon returned to engraving and sketching views of Dubuque and the surrounding area. Later still, he became active in the business of buying and shipping grain, losing a fortune on the wheat market.

Although Simplot never regained his financial position, he was revered as a community leader and remembered as an aristocrat with a flair for fastidious dressing. In his later years, he relished his role in Dubuque’s Early Settlers’ Association where he served as president and secretary for many years. In 1895, the Settlers voted to create a monument to honor Julien Dubuque. They turned to Simplot to design the limestone tower.

Simplot lived out his days in the Dubuque home of his son Alvin where Simplot delighted in serving up batches of French toast and speaking his native French language, according to grandson John. John described his grandfather as a gentle, humble man despite his impressive education and family wealth. “My mother accidentally burned a hole in his favorite pants while ironing them in preparation for a Civil War talk. She said he just shrugged it off without getting upset and found some other pants to wear.”

Alexander Simplot died on October 21, 1914 at the age of 77 and was buried in the Civil War section of Dubuque’s Linwood Cemetery – surrounded by graves of Union soldiers, high on a bluff overlooking Dubuque and his beloved Mississippi River.

Comment here