A window sign requesting an ice delivery would look pretty strange in the 21st century, but back in the 1800s and early 1900s, the signal for the iceman would have been commonplace. Ice harvesting and ice sales were big business before the invention of modern methods of refrigeration.

Kitchens across the country were once equipped with iceboxes: upright, wooden coolers built with hollow walls lined with tin or zinc and packed with insulation. A compartment near the top of the box held a solid block of ice, allowing cold air to circulate underneath and throughout food storage areas. A drip tray at the bottom of the icebox caught water from the melting ice and had to be emptied at least once a day.

When the ice melted away, the delivery request sign – turned to indicate the weight of the desired chunk of ice – was placed in a window to signal the iceman. He would chip a block to the requested size, hoist the ice onto his shoulder with a pair of ice tongs, and haul it into the customer’s kitchen. Ice was cheap by today’s standards; in 1876 in Dubuque, fifteen pounds of ice delivered daily cost $.50 a week, while a daily delivery of a thirty-five-pound block set a household back $1.00 each week.

The short harvesting season made the commercial ice industry extremely competitive. The Iowa Supreme Court had to step in when ice vendors along the Mississippi River became territorial about the areas they planned to use for future ice harvesting. In 1901, the Court ruled that no one could stake out a claim on the banks of a river or stream prior to it being frozen and ready for cutting.

The commercial ice-harvesting season was intense. Often men worked ten-hour days, seven days a week cutting ice and moving heavy blocks into an icehouse. Sometimes, the backbreaking labor continued into the night, and workers cut ice by the light of torches and bonfires. Once the season got underway, the harvest continued non-stop until the icehouse was full.

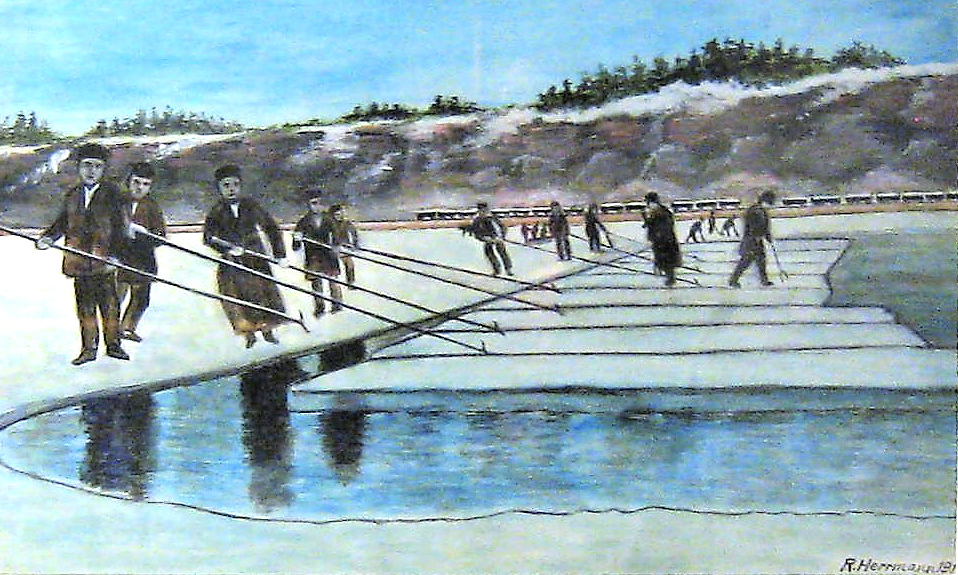

Ice harvesters faced occupational hazards. Sometimes they fell into frigid water or cut their half-frozen bodies with sharp tools of the trade. Danger aside, the actual process of harvesting ice was a well thought out process. When the ice was about 14-18 inches thick, horse-drawn scrapers and men with shovels cleared snow from the area to be harvested.

After the ice field was marked into a grid, teams of horses pulled saws across the ice to cut deep grooves. Men with long handsaws finished cutting the ice into large panels called floats. An expert sawyer could cut an inch or more with each stroke of his saw.

Men wielded pike poles to guide the floats down an open channel cut in the ice. Steel bars called spuds were used to break the floats into individual ice cakes. Finally, blocks of ice were hauled to the icehouse on sleds, wagons, or steam-powered conveyor systems. Icehouse workers stacked the ice carefully, sprinkling each layer with sawdust for insulation and to prevent the blocks from sticking together.

In 1885, Dubuque’s Cushing, Fischer, and Co. employed 250 men and 40 teams of horses to harvest ice. Pier and Ackerman used 30 teams and 150 men to cut ice on Lake Peosta, filling three ice houses at the foot of 14th St. with 15,000 tons of ice. The company also filled three icehouses belonging to the breweries of Heeb and Glab.

Ice harvesting was still big business along the Mississippi River into the 1920s. A Telegraph Herald news article from February 12, 1924 reported the opening of the ice harvesting season on the river:

Dubuque’s ice harvest is now in progress. It isn’t what it used to be in the good old days which preceded the general introduction of the ice manufacturing machines and the refrigeration plants. It is enough, however, to supply employment for a considerable number of men at a time when the demand for employment is strongest. It is estimated that the cut this season will be about 40,000 tons.

A cubic foot of ice weighs 57 pounds and 8 ounces. It will thus be seen that over one million cakes of ice a foot wide, a foot square and 15 inches deep will be removed from the river at Dubuque during the present harvest. Two-thirds of this amount will be consumed locally. The remainder will be shipped to points within 150 miles of Dubuque or used in the refrigeration of railroad cars.

The “natural ice” business faced stiff competition when electric refrigeration cooling systems were invented in the 1900s and manufactured “plant ice” became plentiful year round. Many claimed that “artificial ice” made in plants was cleaner and safer than ice harvested from rivers and lakes, and public opinion began to turn against natural ice. Natural ice companies were forced to convert to producing plant ice in order to remain profitable.

Ice harvesting made a short comeback when the U.S. entered World War I in 1917. During the war, the government promoted the use of natural ice so ammonia and coal needed to produce plant ice could be diverted to the production of munitions. The natural ice industry began to collapse after the war, and icehouses across the country were abandoned.

Electric refrigerators and freezers invented in the early 1900s became more reliable over time, and by 1940, more than five million had been sold. In 1941, Dubuque’s Conlin and Kearns’ ice crew had diminished to just fifty while Mulgrew and Co. employed sixty who were expected to finish the harvest in just four days. Although natural ice continued to be used in rural areas, by the middle of the 20th century, most households were able to freeze their own ice, and very little remained of the once-bustling commercial ice industry.

This article is part of the Shades of Dubuque series, sponsored by Trappist Caskets, hand-made and blessed by the monks at New Melleray Abbey.

Comment here