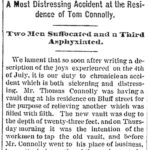

The tale of three men named Thomas began on a Thursday morning in July 1877, the day after the festivities of the 4th. Work activities were resuming in Dubuque following a day of leisure and celebration. Thomas Connolly bade his wife, Ellen, his two-year-old daughter, Annie, and newborn son, Maurice, good-bye as he left their home at 655 Bluff St. Perhaps Thomas Connolly was already thinking of the tasks before him at his carriage company located on the southwest corner of Seventh and Iowa Streets. Business was good. The company had made a name for itself manufacturing carriages, buggies, and sleighs.

But before heading off to work, Thomas Connolly stopped in his back yard to speak with Thomas Harran and Thomas Kelly, two fellow Irishmen he had hired to dig a new privy pit behind his home. The pit had already been dug to a depth of 23 feet. All that remained was to tap into the old vault which was completely filled with filth. Mr. Connolly cautioned the men, reminding them to take care when uniting the two vaults as gas from the old pit was dangerous and might suffocate them. He gave the men an iron bar to puncture the space between the two pits.

Thomas Harran, the elder of the two workmen, put his tools in a tub and lowered them and a ladder down into the new vault. He then got into the tub and had himself lowered as well. Harran climbed up the ladder that he had positioned at the bottom of the vault and, ignoring Connolly’s iron bar, swung a pick to begin the task of connecting the two privy pits. Suddenly, he broke through into the old vault. Thick liquid filth and toxic gases rushed through the opening, knocking Harran off the ladder to the bottom of the pit where he hit his head.

Young Thomas Kelly called for help. When Charles Davis, a carpenter working nearby, appeared, Kelly insisted on being lowered down into the shaft. Kelly was immediately overcome by fumes and fell out of the tub, landing headfirst in the rising tide of filth. Soon, only his legs were visible.

J. Barrett and Mr. Connolly’s hired girl heard the commotion and hurried to see what had happened. At his insistence, they lowered Davis down into the shaft. When Davis reached the drowning men, he too became overcome by fumes and signaled to be hauled back up. When he reached the top, he collapsed, comatose and nearly asphyxiated.

Almost a half hour later, Harran and Kelly were pulled from the filth with grappling hooks. But it was too late. Both men were dead. Funerals for the two men were held the next day.

The Dubuque Herald reported, “The funerals of both will be held at 2 o’clock this Friday afternoon. That of Mr. Harran will be in charge of the St. Vincent de Paul society of which he was a member, the services to be held at St. Patrick’s church. The funeral of Thomas Kelly will be held at the Cathedral. The remains of both will be interred in Key West cemetery.”

At the time of his death, Thomas Harran lived at 1448 Washington St. with his wife Margaret. He had a stepdaughter, Bridget, who was married to James Roberts, a clerk with the Illinois Central Railroad. After her husband’s death, Margaret moved to the Roberts’ Grandview Ave. home where she no doubt missed the company of her husband but enjoyed living close to her three grandchildren. Margaret died in 1890 and was buried near her husband in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Key West.

Thomas Kelly was thirty-years-old at the time of his death. The July 1877 newspaper article reported he had come to the United States eight years before the disaster. He was a relative of Dubuquer Hugh Talty, whose wife was the former Mary Ann Kelly. Thomas had married his wife, Maggie, just five months before his untimely death.

There is a marker for Kelly behind 345 Bluff St. The inscription reads:

Thomas Kelly

Died

July 5, 1877

Aged 30 Years

A Native of County Clare

IRELAND

May his soul rest in Peace

Amen

Erected by his Wife

Maggie Kelly

Jennifer Mack, University of Iowa bioarchaeologist, suspects Thomas Kelly was actually buried in the old Third St. Cemetery on the bluff behind St. Raphael’s Cathedral. “I have always been perplexed by the Thomas Kelly grave marker,” Jennifer wrote. “I got permission from the previous owners [of 345 Bluff St.] to poke around in the backyard. We wanted to probe around and under the stone to see if there was a void or loose soil to indicate a grave shaft. We couldn’t get the probe in the ground. Either there was a bunch of cement around the marker base, or it was all rocks – I can’t recall which one. In any case, I [rather] doubt that Thomas is back there. At the time we investigated, I thought it was likely that he was buried in the Third Street Cemetery, and that the stone just got moved down the hill at some point.”

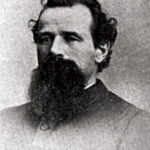

In the years after the accident, the Connollys had two more daughters: Martha, who died as an infant, and Eleanor. In 1891, the family moved from their Bluff St. home to a mansion Connolly had built near Jackson Park on Iowa St. The elegant home boasted the finest craftsmanship and materials as well as one of the city’s only carriage steps, a raised platform that allowed visitors to exit their carriages directly into the home without stepping on the ground. Connolly died on December 28, 1903, at the age of sixty-six. He was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

So ends the tale of the three men named Thomas. Dead for many years, they are remembered for the tragic intersection of their lives on a fateful July morning more than 140 years ago.

This article is part of the Shades of Dubuque series, sponsored by Trappist Caskets, hand-made and blessed by the monks at New Melleray Abbey.

Comment here